It’s great to create tools that serve as a foundation for developer projects. Huge impact. Last year, we’ve released Chokidar 3 file watcher and started saving terabytes of NPM traffic daily while improving overall security of JS ecosystem. You may have Chokidar on your machine if you’re coding in VSCode.

After this, i’ve started diving more into cryptography. It’s very useful to know how those algorithms work, to be able to verify them & to create safe systems.

It was immediately clear that Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) libraries must be improved. In this post i’ll describe how to make one of the fastest JS implementations of secp256k1, that can be audited by non-cryptographers. The initial working code will fit in 898 bytes.

- State of cryptography in JS

- Naïve first take

- Public keys

- Signatures

- Randomness and PlayStation

- Fighting timing attacks

- BigInts, JIT, GC and other scary words

- Projecting…coordinates?

- Precomputes and wNAF

- Endomorphism

- Endgame: combining everything

- Extra tricks

- Final thoughts and source code

State of cryptography in JS

The state of JavaScript cryptography can be summed up in one word: “sad”:

- Dependency Hell: Many libraries are bloated with dependencies. As i’ve mentioned before, every dependency is a potential security vulnerability — any underlying package could get hacked & malwared. This is unacceptable for cryptographic primitives, which are made to defend user secrets.

- Bad WebCrypto: The

window.cryptostandard is complicated and lacks support for popular curves like secp256k1. Those APIs which do exist are terrible and make it easy to shoot oneself in foot - Unverifiable WASM: While WASM offers performance benefits, it lacks transparency and auditability. There is no infrastructure for reproducible builds and code signing. Everybody just downloads opaque binaries, which could easily be infested

- Modular Arithmetic Issues: JavaScript’s % operator is a remainder operator, not a true modulo, which necessitates re-implementing basic operations.

Naïve first take

Taking all of this into consideration, i’ve decided to create TypeScript libraries that don’t use dependencies & are simple to audit for everyone. Having no “deep” math background, it wasn’t that simple. Cloudflare blog post, Nakov’s book and Andrea’s blog post have all been very useful.

And you can’t just go ahead and read through the code. Almost every implementation — even in Haskell — work with unreadable and highly optimized code. In a real world, we’ll see something more like:

for (i = 254; i >= 0; --i) {

r = (z[i >>> 3] >>> (i & 7)) & 1;

sel25519(a, b, r);

sel25519(c, d, r);

A(e, a, c);

Z(a, a, c);

A(c, b, d);

Z(b, b, d);

S(d, e);

}

The only lib i’ve found useful was fastecdsa.py. Unfortunately, it’s rare for libraries to be built on top of big integers. It’s much easier to reason with numbers, instead of byte arrays, which everyone prefers.

Public keys

We will start with a function that takes private key and generates public key from it.

To generate a public key from a private key using elliptic curve cryptography (ECC), you need to perform elliptic curve point multiplication. This involves multiplying the base (generator) point

G by the private key p to obtain the public key P:

P = G × p

Multiplication can be thought of as repeated addition of the base point G+G+G... - p times.

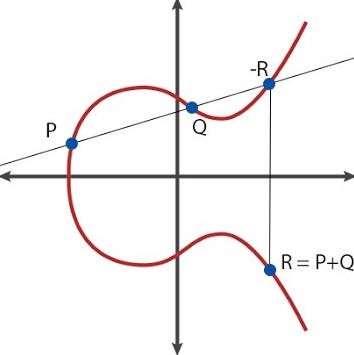

How do we add (x1, y1) + (x2, y2) to get (x3, y3)?

- Imagine drawing a straight line between the two points P and Q on the elliptic curve

- This line will generally intersect the curve at a third point.

- Reflect this third point vertically (i.e., flip the y-coordinate) to get the resulting point Q, resulting in

(x3, -y3)- This reflection is necessary to ensure that point subtraction works correctly; for example, when computing R - Q, you actually add R to the negation of Q. By flipping Q’s y-coordinate and drawing the line between R and -Q, you obtain the expected result P.

- There is a special case for doubling. When point is added to itself, we can’t draw a straight line. Instead, we calculate the slope (λ, lambda) of the tangent line at the point.

- There is a special case for adding point to same flipped point:

P + -Pshould equal to0(special point-at-infinity)

In math terms (source):

- if

x1 != x2:λ = (y2-y1)/(x2-x1)x3 = λ^2 - x1 - x2y3 = λ(x1 - x3) - y1

- if

x1 = x2andy1 = y2(point doubling):λ = (3*x1^2+a)/(2y1)x3 = λ^2 - 2*x1y3 = λ(x1 - x3) - y1

Simple, but not quite. Keep in mind: we’re working in a finite field over some big prime P. This basically means all operations — additions, multiplications, subtractions — would be done modulo P. And, there is no classic division in finite fields. Instead, a modular multiplicative inverse is used. It is most efficiently calculated by iterative version of Euclid’s GCD algorithm.

Let’s code this:

// PART 1: unsafe pub

// secp256k1 curve parameters. Verify using https://www.secg.org/sec2-v2.pdf

const _256 = 2n ** 256n;

const P = _256 - 0x1000003d1n; // curve's field prime

const N = _256 - 0x14551231950b75fc4402da1732fc9bebfn; // curve (group) order

const err = (m = ''): never => { throw new Error(m); }; // error helper

const M = (a: bigint, b: bigint = P) => {

// mod division

const r = a % b;

return r >= 0n ? r : b + r; // a % b = r

};

// prettier-ignore

const inv = (num: bigint, md: bigint): bigint => { // modular inversion

if (num === 0n || md <= 0n) err('no inverse n=' + num + ' mod=' + md); // no neg exponent for now

let a = M(num, md), b = md, x = 0n, y = 1n, u = 1n, v = 0n;

while (a !== 0n) { // uses euclidean gcd algorithm

const q = b / a, r = b % a; // not constant-time

const m = x - u * q, n = y - v * q;

b = a, a = r, x = u, y = v, u = m, v = n;

}

return b === 1n ? M(x, md) : err('no inverse'); // b is gcd at this point

};

// Point in 2d affine (x, y) coordinates

interface AffinePoint {

x: bigint;

y: bigint;

}

const affine = (x: bigint, y: bigint): AffinePoint => ({ x: x, y: y });

const Point_ZERO = { x: 0n, y: 0n }; // Point at infinity aka identity point aka zero

// Adds point to itself. https://hyperelliptic.org/EFD/g1p/auto-shortw.html

const pdouble = (a: AffinePoint) => {

const X1 = a.x, Y1 = a.y;

// Calculates slope of the tangent line

const lam = M(3n * X1 ** 2n * inv(2n * Y1, P)); // λ = (3x₁² + a) / (2y₁)

const X3 = M(lam * lam - 2n * X1); // x₃ = λ² - 2x₁

const Y3 = M(lam * (X1 - X3) - Y1); // y₃ = λ * (x₁ - x₃) - y₁

return affine(X3, Y3);

};

// Adds point to other point. https://hyperelliptic.org/EFD/g1p/auto-shortw.html

const padd = (a: AffinePoint, b: AffinePoint): AffinePoint => {

const X1 = a.x, Y1 = a.y, X2 = b.x, Y2 = b.y;

if (X1 === 0n || Y1 === 0n) return b;

if (X2 === 0n || Y2 === 0n) return a;

if (X1 === X2 && Y1 === Y2) return pdouble(a); // special case

if (X1 === X2 && Y1 === M(-Y2)) return Point_ZERO; // special case

const lam = M((Y2 - Y1) * inv(X2 - X1, P));

const X3 = M(lam * lam - X1 - X2);

const Y3 = M(lam * (X1 - X3) - Y1);

return affine(X3, Y3);

};

/** Generator / base point */

// G x, y values taken from official secp256k1 document: https://www.secg.org/sec2-v2.pdf

const Gx = 0x79be667ef9dcbbac55a06295ce870b07029bfcdb2dce28d959f2815b16f81798n;

const Gy = 0x483ada7726a3c4655da4fbfc0e1108a8fd17b448a68554199c47d08ffb10d4b8n;

const Point_BASE = affine(Gx, Gy);

const mul_unsafe = (q: AffinePoint, n: bigint) => {

let curr = affine(q.x, q.y);

let p = Point_ZERO;

while (n > 0n) {

if (n & 1n) p = padd(p, curr);

curr = pdouble(curr);

n >>= 1n;

}

return p;

};

const _getPublicKey = (privateKey: bigint): AffinePoint => {

return mul_unsafe(Point_BASE, privateKey);

};

Yay, it works.

Signatures

A good ECC library should also be able to produce & verify signatures. Formulas for ECDSA sigs are simple.

Let:

mbe the hash of the message, converted to a number.dbe the private key, converted to a number.kbe the secret (random) nonce number.Gbe the generator point.nbe the order of the curve.

Then the signing process is defined as:

(x_1, y_1) = G × k

r = x_1 mod n

s = k^-1 ⋅ (m + d⋅r) mod n

For verification, given:

r, sas the signature outputsQas the public key corresponding to the private keyd.

u_1 = s^-1 ⋅ m mod n

u_2 = s^-1 ⋅ r mod n

(x_2, y_2) = G × u_1 + Q × u_2

x_2 mod n == r

Let’s code them:

// PART 2: unsafe sigs

interface Signature {

r: bigint;

s: bigint;

recovery?: number;

}

// Convert Uint8Array to bigint, big endian

// prettier-ignore

const bytesToNumBE = (bytes: Uint8Array): bigint => {

const hex = Array.from(bytes).map((e) => e.toString(16).padStart(2, "0")).join("");

return hex ? BigInt("0x" + hex) : 0n;

};

// Get random k from CSPRNG.

// (rand32 mod N) is naive version

// (rand48 mod N-1)+1 is ours, proper version.

// +16 more bytes are fetched to make modulo bias small.

// (mod N-1)+1 is done to eliminate 0 from output.

const randK = (): bigint => {

// @ts-ignore

const b = crypto.getRandomValues(new Uint8Array(48));

const num = M(bytesToNumBE(b), N - 1n);

return num + 1n;

};

const _sign = (msgh: Uint8Array, priv: bigint): Signature => {

const m = bytesToNumBE(msgh);

const d = priv;

let r = 0n;

let s = 0n;

let q;

do {

const k = randK();

const ik = inv(k, N);

q = mul_unsafe(Point_BASE, k);

r = M(q.x, N);

s = M(ik * M(m + d * r, N), N);

} while (r === 0n || s === 0n);

if (s > N >> 1n) {

s = M(-s, N);

}

return { r, s };

};

const _verify = (sig: Signature, msgh: Uint8Array, pub: AffinePoint): boolean => {

const h = M(bytesToNumBE(msgh), N);

const is = inv(sig.s, N);

const u1 = M(h * is, N);

const u2 = M(sig.r * is, N);

const G_u1 = mul_unsafe(Point_BASE, u1);

const P_u2 = mul_unsafe(pub, u2);

const R = padd(G_u1, P_u2);

if (R.x === 0n && R.y === 0n) return false;

const v = M(R.x, N);

return v === sig.r;

};

Randomness and PlayStation

You may have noticed we’re using this weird algorithm for generating a random k.

Why is that important?

Turns out, if you reuse k to sign two different messages under the same private key,

your key would get exposed and leaked. It’s really bad.

There are two common ways of solving this situation:

- Fetch

kfrom a secure source of randomness (CSPRNG)- It was popular, until PlayStation 3 private keys got leaked, because PS3 CSPRNG randomness was not really random

- This is a big problem on some devices which are not able to generate enough entropy

- Entropy generator could also be malicious (backdoored)

- Calculate

kfromprivandmsghdeterministically. RFC6979 does exactly that, by using HMAC-DRBG- Got massive adoption these days

- The DRBG seems a bit complicated: perhaps, if the RFC was created later, they could have just used something like HKDF

- While the method protects against bad randomness, it does not protect against so-called “fault attacks”.

Suppose in the code above, an error happens in

invfor some values ofinv(k, N). It would get broken and produce garbage, leaking private keys.

In the article we implement 1 for simplicity, while in the library we implement 2. Article’s version has some important tricks, like using FIPS 186 4.1 technique to fetch more randomness than necessary and eliminate zeros from produced values.

Combining 1 and 2 is the best approach and described in RFC6979 3.6 (additional k). It’s called “hedged signatures” / “deterministic signatures with noise” / “extra entropy”.

Fighting timing attacks

Timing attack are a type of side-channel attack where an adversary measures how long your algorithms take to execute, leveraging variations in execution time to infer secret information.

Consider a web app that signs user messages with a private key — if the processing times for a high volume of requests (say, 100,000 calls to a /sign endpoint) differ based on the input, an attacker could potentially deduce the private key. More advanced side-channel methods even analyze power consumption to extract secrets.

To mitigate these risks, cryptographic software must operate in constant time, making sure that operations like character-by-character string comparisons always take the same duration regardless of input. Fortunately, such timing attacks are relatively uncommon, and breaches are more likely to result from vulnerabilities in third-party dependencies.

Let’s see if we’re protected against timing attacks right now:

const measure = (label: string, fn: any) => {

console.time(label);

fn();

console.timeEnd(label);

};

measure("small DA", () => mul_unsafe(Point_BASE, 2n));

measure("large DA", () => mul_unsafe(Point_BASE, 2n ** 255n - 19n));

// small DA: 0.053ms

// large DA: 10.377ms

// getPublicKey_unsafe 1: 9.218ms

// getPublicKey_unsafe 2: 0.076ms

// sign_slow_unsafe: 7.132ms

// verify_slow: 13.986ms

Depending on a private key, it could take up to 190x more time to compute the public key. Seems like we are not protected. How could this be solved?

- Private key is 256 bits: 256 zeros or ones

- Fast keys have many zeros and a few ones e.g.

0000001000000 - Slow keys have less zeros e.g.

1111011101111111 - Right now we only add points with each other when

1is present - We need to ensure that we also do it when bit is

0

Very simple idea: when 1 is present, do business as usual. When 0 is present, add something to a fake point:

// PART 3: safe mul

// Constant Time multiplication

const getPowers = (q: AffinePoint) => {

let points: AffinePoint[] = [];

for (let bit = 0, dbl = q; bit <= 256; bit++, dbl = pdouble(dbl)) {

points.push(dbl);

}

return points;

};

const mul_CT_slow = (q: AffinePoint, n: bigint) => {

const pows = getPowers(q);

let p = Point_ZERO;

let f = Point_ZERO; // fake point

for (let bit = 0; bit <= 256; bit++) {

const at_bit_i = pows[bit];

if (n & 1n) p = padd(p, at_bit_i);

else f = padd(f, at_bit_i);

n >>= 1n;

}

return p;

};

Let’s measure getPublicKey now.

measure("small CT", () => mul_CT_slow(Point_BASE, 2n));

measure("large CT", () => mul_CT_slow(Point_BASE, 2n ** 255n - 19n));

// small CT: 9.409ms

// large CT: 9.381ms

Now it is slower on average, but at least it’s “constant-time”.

BigInts, JIT, GC and other scary words

Native JS BigInts are often labeled “unsuitable for cryptography” because their operations aren’t guaranteed to be constant-time. However, my tests indicate that this constant-timeness holds up to approximately 1024-bit numbers. Since most of our operations occur modulo P and the operands involved in addition or multiplication remain below 1024 bits, the native BigInt implementation handles these values efficiently without noticeable timing differences. In fact, executing a timing attack on an algorithmically correct Point#multiply would require exponentially more effort, which suggests that creating an alternative library focused solely on achieving constant-time performance is unnecessary.

It’s also important to acknowledge that JavaScript is a dynamic language, and there are inherent factors that can disrupt any constant-time guarantees, such as:

- Garbage collection: A function that normally executes in 5ms might take 7ms when the JS engine performs object reclamation.

- Just-in-time compilation: The multiple optimizations and deoptimizations by modern JIT compilers can lead to variation in execution times based on context.

Thus, whether we use native BigInts or a custom implementation like bn.js (which is over 6,000 lines of code), obtaining true constant-time behavior in JavaScript is unattainable.

“Constant-time” is impossible in javascript. That’s it. The best we can do is an algorithmic constant-time & removing dependencies which make us more likely to get malwared.

Projecting…coordinates?

Right now, our call structure consists of:

- Initialization: 256 doubles

- Multiplication: 256 adds

Let’s dive into what actually happens inside the add and double operations. Both of these functions perform several additions and multiplications, and crucially, each includes one invert (i.e., finite field division). Profiling reveals that invert is extremely slow — typically 20 to 100 times slower than a multiplication—which means each multiplication might involve up to 512 inverts.

Projective (or homogeneous) coordinates provide an elegant solution by eliminating these costly inversions from both functions. Note that our default x, y coordinates are in Affine form. In projective coordinates, a point is represented by the triple (X, Y, Z); conversion between representations is straightforward. To convert from Projective to Affine, we use:

Ax = X / Z;

Ay = Y / Z;

Recall that m/n = m * inv(n).

Converting a point to Projective form is even simpler: we set Z to 1, and copy X and Y directly.

We’re also planning to implement dedicated Point#double & add methods using the Renes-Costello-Batina 2015 exception-free addition / doubling formulas. “Exception-free” means those formulas avoid conditional branches, such as checking whether two points are identical (or zero), as seen in our initial mul implementation. Using such formulas is important for constant-timeness.

Finally, we will modify our getPrecomputes function to operate exclusively on Point objects, converting them back to Affine form via Point#toAffine() just before returning results.

We’ll change getPrecomputes to work with Point everywhere. And just before return we’ll execute Point#toAffine() to get AffinePoint.

// PART 4: proj mul

const CURVE = { P: P, n: N, a: 0n, b: 7n };

const equals = (a: AffinePoint, b: AffinePoint) => a.x === b.x && a.y === b.y;

// Point in 3d projective (x, y, z) coordinates

class Point {

px: bigint;

py: bigint;

pz: bigint;

constructor(x: bigint, y: bigint, z: bigint) {

this.px = x;

this.py = y;

this.pz = z;

}

/** Create 3d xyz point from 2d xy. Edge case: (0, 0) => (0, 1, 0), not (0, 0, 1) */

static fromAffine(p: AffinePoint): Point {

return p.x === 0n && p.y === 0n ? new Point(0n, 1n, 0n) : new Point(p.x, p.y, 1n);

}

toAffine(iz: bigint = inv(this.pz, P)): AffinePoint {

const x = M(this.px * iz);

const y = M(this.py * iz);

return { x, y };

}

// prettier-ignore

add(other: Point) {

const { px: X1, py: Y1, pz: Z1 } = this;

const { px: X2, py: Y2, pz: Z2 } = other;

const { a, b } = CURVE;

let X3 = 0n, Y3 = 0n, Z3 = 0n;

const b3 = M(b * 3n); // step 1

let t0 = M(X1 * X2), t1 = M(Y1 * Y2), t2 = M(Z1 * Z2), t3 = M(X1 + Y1);

let t4 = M(X2 + Y2); // step 5

t3 = M(t3 * t4); t4 = M(t0 + t1); t3 = M(t3 - t4); t4 = M(X1 + Z1);

let t5 = M(X2 + Z2); // step 10

t4 = M(t4 * t5); t5 = M(t0 + t2); t4 = M(t4 - t5); t5 = M(Y1 + Z1);

X3 = M(Y2 + Z2); // step 15

t5 = M(t5 * X3); X3 = M(t1 + t2); t5 = M(t5 - X3); Z3 = M(a * t4);

X3 = M(b3 * t2); // step 20

Z3 = M(X3 + Z3); X3 = M(t1 - Z3); Z3 = M(t1 + Z3); Y3 = M(X3 * Z3);

t1 = M(t0 + t0); // step 25

t1 = M(t1 + t0); t2 = M(a * t2); t4 = M(b3 * t4); t1 = M(t1 + t2);

t2 = M(t0 - t2); // step 30

t2 = M(a * t2); t4 = M(t4 + t2); t0 = M(t1 * t4); Y3 = M(Y3 + t0);

t0 = M(t5 * t4); // step 35

X3 = M(t3 * X3); X3 = M(X3 - t0); t0 = M(t3 * t1); Z3 = M(t5 * Z3);

Z3 = M(Z3 + t0); // step 40

return new Point(X3, Y3, Z3);

}

double() {

return this.add(this);

}

negate() {

return new Point(this.px, M(-this.py), this.pz);

}

}

const Proj_ZERO = Point.fromAffine(Point_ZERO);

const Proj_BASE = Point.fromAffine(Point_BASE);

const getPowersProj = (qxy: AffinePoint): Point[] => {

const q = Point.fromAffine(qxy);

let points: Point[] = [];

for (let bit = 0, dbl = q; bit <= 256; bit++, dbl = dbl.double()) {

points.push(dbl);

}

return points;

};

const mul_CT = (q: AffinePoint, n: bigint) => {

const pows = getPowersProj(q);

let p = Proj_ZERO;

let f = Proj_ZERO; // fake point

for (let bit = 0; bit <= 256; bit++) {

const at_bit_i = pows[bit];

if (n & 1n) p = p.add(at_bit_i);

else f = f.add(at_bit_i);

n >>= 1n;

}

return p.toAffine();

};

Let’s see how this improves things for us:

CT proj: 1.499ms

Woah! That’s 6x improvement for multiply.

Precomputes and wNAF

Currently, we do 256 point additions, for each of 256 bits of a scalar, by which

Point is multiplied.

Simplest optimization would be to cache getPowers method.

This way, powers of G would get precomputed once and for all.

Instead of doing that, let’s get more efficient and split scalar into 4/8/16-bit chunks, pre-compute powers AND additions within those chunks.

w-ary non-adjacent form method (wNAF) allows to do exactly that. Instead of caching 256 points like we did before, we would cache 520 (W=4), 4224 (W=8) or 557056 (W=16) points.

We could also do this with alternative, “windowed method”, but wNAF saves us ½ RAM and is 2x faster in init time. The reason for this is that wNAF does addition and subtraction — and for subtraction it simply negates point, which can be done in constant time.

// PART 5: wnaf mul

const W = 8; // Precomputes-related code. W = window size

// prettier-ignore

const precompute = () => { // They give 12x faster getPublicKey(),

const points: Point[] = []; // 10x sign(), 2x verify(). To achieve this,

const windows = 256 / W + 1; // app needs to spend 40ms+ to calculate

let p = Proj_BASE, b = p; // a lot of points related to base point G.

for (let w = 0; w < windows; w++) { // Points are stored in array and used

b = p; // any time Gx multiplication is done.

points.push(b); // They consume 16-32 MiB of RAM.

for (let i = 1; i < 2 ** (W - 1); i++) { b = b.add(p); points.push(b); }

p = b.double(); // Precomputes don't speed-up getSharedKey,

} // which multiplies user point by scalar,

return points; // when precomputes are using base point

}

let Gpows: Point[] | undefined = undefined; // precomputes for base point G

// prettier-ignore

const wNAF = (n: bigint): { p: Point; f: Point } => { // w-ary non-adjacent form (wNAF) method.

// Compared to other point mult methods,

const comp = Gpows || (Gpows = precompute()); // stores 2x less points using subtraction

const neg = (cnd: boolean, p: Point) => { let n = p.negate(); return cnd ? n : p; } // negate

let p = Proj_ZERO, f = Proj_BASE;// f must be G, or could become I in the end

const windows = 1 + 256 / W; // W=8 17 windows

const wsize = 2 ** (W - 1); // W=8 128 window size

const mask = BigInt(2 ** W - 1); // W=8 will create mask 0b11111111

const maxNum = 2 ** W; // W=8 256

const shiftBy = BigInt(W); // W=8 8

for (let w = 0; w < windows; w++) {

const off = w * wsize;

let wbits = Number(n & mask); // extract W bits.

n >>= shiftBy; // shift number by W bits.

if (wbits > wsize) { wbits -= maxNum; n += 1n; } // split if bits > max: +224 => 256-32

const off1 = off, off2 = off + Math.abs(wbits) - 1; // offsets, evaluate both

const cnd1 = w % 2 !== 0, cnd2 = wbits < 0; // conditions, evaluate both

if (wbits === 0) {

f = f.add(neg(cnd1, comp[off1])); // bits are 0: add garbage to fake point

} else { // ^ can't add off2, off2 = I

p = p.add(neg(cnd2, comp[off2])); // bits are 1: add to result point

}

}

return { p, f } // return both real and fake points for JIT

}; // !! you can disable precomputes by commenting-out call of the wNAF() inside Point#mul()

const mul_G_wnaf = (n: bigint) => {

const { p, f } = wNAF(n);

f.toAffine(); // result ignored

return p.toAffine();

};

Let’s see where this lands us:

mul_G_wnaf: 0.196ms

So, 10x faster; even though init got slightly slower. You may have noticed that it’s possible to adjust wNAF W parameter: it specifies how many precomputed points we’ll calculate.

Endomorphism

Let’s get hardcore. But not too much — otherwise, the code would be unauditable.

To improve performance even more, we must look at the properties at our underlying elliptic curve.

secp256k1 is Koblitz curve (e.g. Short Weierstrass curve with a=0).

Koblitz curves allow using efficiently-computable GLV endomorphism ψ:

- GLV endomorphism ψ transforms a point:

P = (x, y) ↦ ψ(P) = (β·x mod p, y) - GLV scalar decomposition transforms a scalar:

k ≡ k₁ + k₂·λ (mod n) - Then these are combined:

k·P = k₁·P + k₂·ψ(P) - Two 128-bit point-by-scalar multiplications + one point addition is faster than one 256-bit multiplication.

Endomorphism uses 2x less RAM, speeds up precomputation by 2x and ECDH / key recovery by 20%. For precomputed wNAF it trades off 1/2 init time & 1/3 ram for 20% perf hit.

Calculating endomorphism is simple (check out code):

- beta: β ∈ Fₚ with β³ = 1, β ≠ 1

- lambda: λ ∈ Fₙ with λ³ = 1, λ ≠ 1

- k ↦ k₁, k₂ is decomposed using splitScalar function, which uses reduced basis vectors.

Gauss lattice reduction calculates them from initial basis vectors

(n, 0), (-λ, 0)

In multiply, we will need to split scalar into two, and then calculate sum of two resulting points.

We can also adjust mul_CT and mul_G_wnaf (to reduce init time / memory by 2x),

but we won’t do that here.

// PART 6: endo

const CURVE_beta =

0x7ae96a2b657c07106e64479eac3434e99cf0497512f58995c1396c28719501een;

// const CURVE_lambda = 0x5363ad4cc05c30e0a5261c028812645a122e22ea20816678df02967c1b23bd72n;

const CURVE_basis = [

[0x3086d221a7d46bcde86c90e49284eb15n, -0xe4437ed6010e88286f547fa90abfe4c3n],

[0x114ca50f7a8e2f3f657c1108d9d44cfd8n, 0x3086d221a7d46bcde86c90e49284eb15n]

];

const divNearest = (a: bigint, b: bigint) => (a + b / 2n) / b;

const splitScalar = (k: bigint) => {

const [[a1, b1], [a2, b2]] = CURVE_basis;

// Use Babai's round-off algorithm:

// Calculate continuous coordinates in the basis

const c1 = divNearest(b2 * k, N);

const c2 = divNearest(-b1 * k, N);

// Calculate the closest lattice point to (k, 0)

// Calculate k1 = k - b1 (mod n) and k2 = -b2 (mod n)

let k1 = M(k - c1 * a1 - c2 * a2, N);

let k2 = M(-c1 * b1 - c2 * b2, N);

const POW_2_128 = 0x100000000000000000000000000000000n; // (2n**128n).toString(16)

const k1neg = k1 > POW_2_128;

const k2neg = k2 > POW_2_128;

if (k1neg) k1 = N - k1;

if (k2neg) k2 = N - k2;

if (k1 > POW_2_128 || k2 > POW_2_128) err("endomorphism failed, k=" + k);

return { k1neg, k1, k2neg, k2 };

};

const mul_endo = (q: AffinePoint, n: bigint) => {

let { k1neg, k1, k2neg, k2 } = splitScalar(n);

let k1p = Proj_ZERO;

let k2p = Proj_ZERO;

let d: Point = Point.fromAffine(q);

while (k1 > 0n || k2 > 0n) {

if (k1 & 1n) k1p = k1p.add(d);

if (k2 & 1n) k2p = k2p.add(d);

d = d.double();

k1 >>= 1n;

k2 >>= 1n;

}

if (k1neg) k1p = k1p.negate();

if (k2neg) k2p = k2p.negate();

k2p = new Point(M(k2p.px * CURVE_beta), k2p.py, k2p.pz);

return k1p.add(k2p).toAffine();

};

This idea was popularized for the curve by Hal Finney. and is described on pages 125-129 of the Guide to ECC, by Hankerson, Menezes and Vanstone.

Endgame: combining everything

Let’s combine 3 different multiplication algorithms to get the fastest of all worlds:

- wNAF can only be used for base / generator point, because we don’t calculate it for others

- Endomorphism is fast, but slower than wNAF. However, we didn’t write endomorphism for fake points in the article. So, it can only be used for cases when timing attacks are not relevant. One such case is verification, which does not operate on private inputs.

- For everything else there is

mul_CT, which is slower than endomorphism, but safe

Additionally, let’s implement getSharedSecret (elliptic curve diffie-hellman), and add

recovery bit to sign() output; to ensure a way to recover public keys from signatures.

// PART 7, final pub + sign + verify + shared

const mul = (q: AffinePoint, n: bigint, safe = true) => {

if (equals(q, Point_BASE)) return mul_G_wnaf(n);

return safe ? mul_CT(q, n) : mul_endo(q, n);

};

function getPublicKey(privateKey: bigint): AffinePoint {

return mul(Point_BASE, privateKey);

}

function sign(msgh: Uint8Array, priv: bigint): Signature {

const m = bytesToNumBE(msgh);

const d = priv;

let r = 0n;

let s = 0n;

let q;

do {

const k = randK();

const ik = inv(k, N);

q = mul(Point_BASE, k);

r = M(q.x, N);

s = M(ik * M(m + d * r, N), N);

} while (r === 0n || s === 0n);

let recovery = (q.x === r ? 0 : 2) | Number(q.y & 1n);

if (s > N >> 1n) {

recovery ^= 1;

s = M(-s, N);

}

return { r, s, recovery };

}

function verify(sig: Signature, msgh: Uint8Array, pub: AffinePoint): boolean {

const h = M(bytesToNumBE(msgh), N);

const is = inv(sig.s, N);

const u1 = M(h * is, N);

const u2 = M(sig.r * is, N);

const G_u1 = mul(Point_BASE, u1);

const P_u2 = mul(pub, u2, false);

const R = padd(G_u1, P_u2);

const v = M(R.x, N);

return v === sig.r;

}

function getSharedSecret(privA: bigint, pubB: AffinePoint): AffinePoint {

return mul(pubB, privA);

}

The benchmarks look like that now:

getPublicKey: 0.234ms

sign: 0.258ms

verify: 1.264ms

While we started with:

getPublicKey_unsafe 1: 12.468ms

getPublicKey_unsafe 2: 0.11ms

sign_slow_unsafe: 9.442ms

verify_slow: 19.073ms

Awesome!

Extra tricks

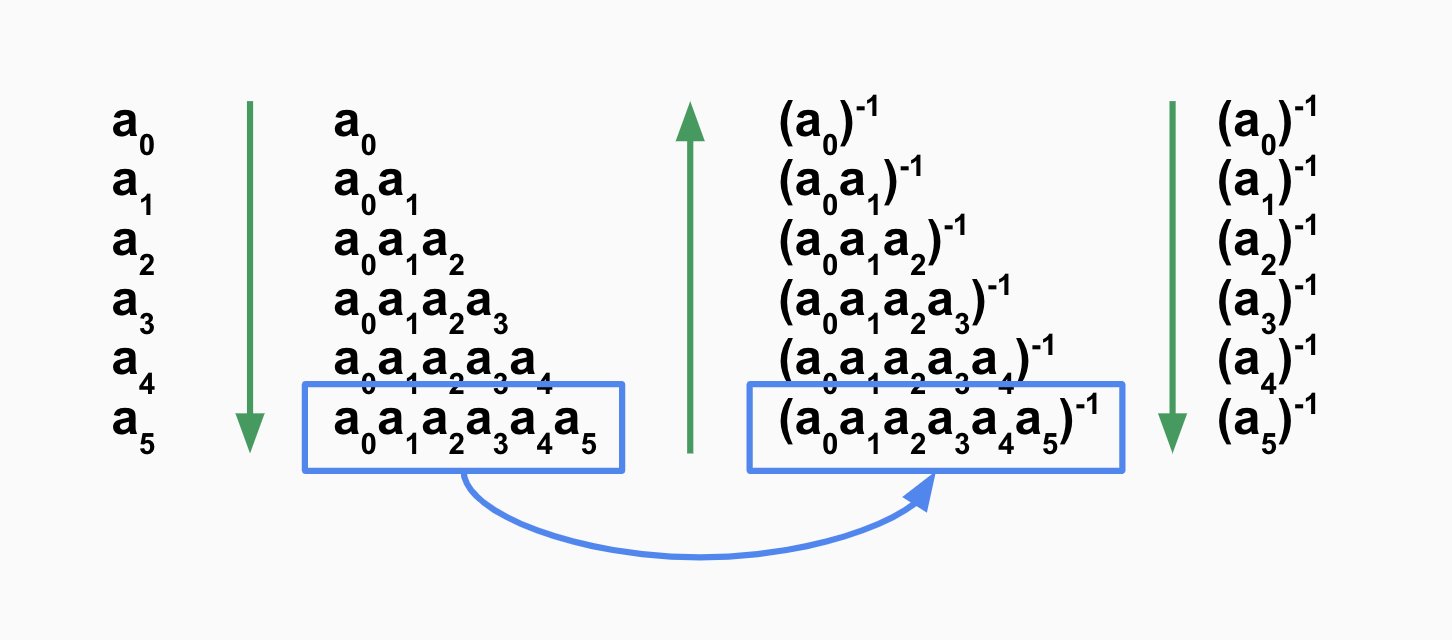

One thing worth mentioning is Montgomery Batch Inversion.

We get a bunch a numbers, do one inverse, and then we apply it to all numbers.

At this point, we don’t really use invert anywhere except for a few places.

function invBatch(nums: bigint[]): bigint[] {

const tmp = new Array(nums.length);

// Walk from first to last, multiply them by each other MOD p

const lastMultiplied = nums.reduce((acc, num, i) => {

if (num === 0n) return acc;

tmp[i] = acc;

return M(acc * num);

}, 1n);

// Invert last element

const inverted = inv(lastMultiplied, P);

// Walk from last to first, multiply them by inverted each other MOD p

nums.reduceRight((acc, num, i) => {

if (num === 0n) return acc;

tmp[i] = M(acc * tmp[i]);

return M(acc * num);

}, inverted);

return tmp;

}

const invPointsBatch = (points: Point[]) => {

return points;

// const points = [p, f];

const inverted = invBatch(points.map((p) => p.pz));

return points.map((p, i) => Point.fromAffine(p.toAffine(inverted[i])));

};

// REPLACE in `mul_G_wnaf`:

// return invPointsBatch([p, f])[0].toAffine();

// REPLACE IN `wNAF`:

// const comp = Gpows || (Gpows = invPointsBatch(precompute()));

The gains are small, but could be used.

One unexpected place is wNAF: we can normalize all precomputed points to have Z=1,

which would slightly improve speed of getPublicKey and sign.

Another useful trick is Multi-Scalar Multiplication (MSM).

It is commonly implemented using Pippenger algorithm.

MSM could be used for calculating addition of many points at once:

aP + bQ + cR + .... It only makes sense to use it with bigger inputs.

Final thoughts and source code

We’ve got sign from unsafe 7.028ms to safe 0.177ms, a 39x speed-up.

All without re-implementing bigints, esoteric math (well, besides endomorphism) and low-level languages. At this point it’s the fastest secp256k1 ECDSA lib in pure JavaScript.

Something like BIP340 Schnorr signatures can easily be implemented on top of these primitives.

- The code from the article is available:

- secp256k1-1kb.min.js — JS, parts 1+2, unsafe, fits in 898 bytes gzipped

- secp256k1.ts — TS, all methods

- noble-secp256k1 — 4kb safe, full-featured library is ready to for use in all kinds of projects.

- noble-curves — larger, generic and safe standard for JS ECC cryptography, with ed25519, BLS12-381, and other algorithms

Join the journey to auditable cryptography via X.com & GitHub.